MODULE 4: INFORMING CONTEXTS. WEEK 7.

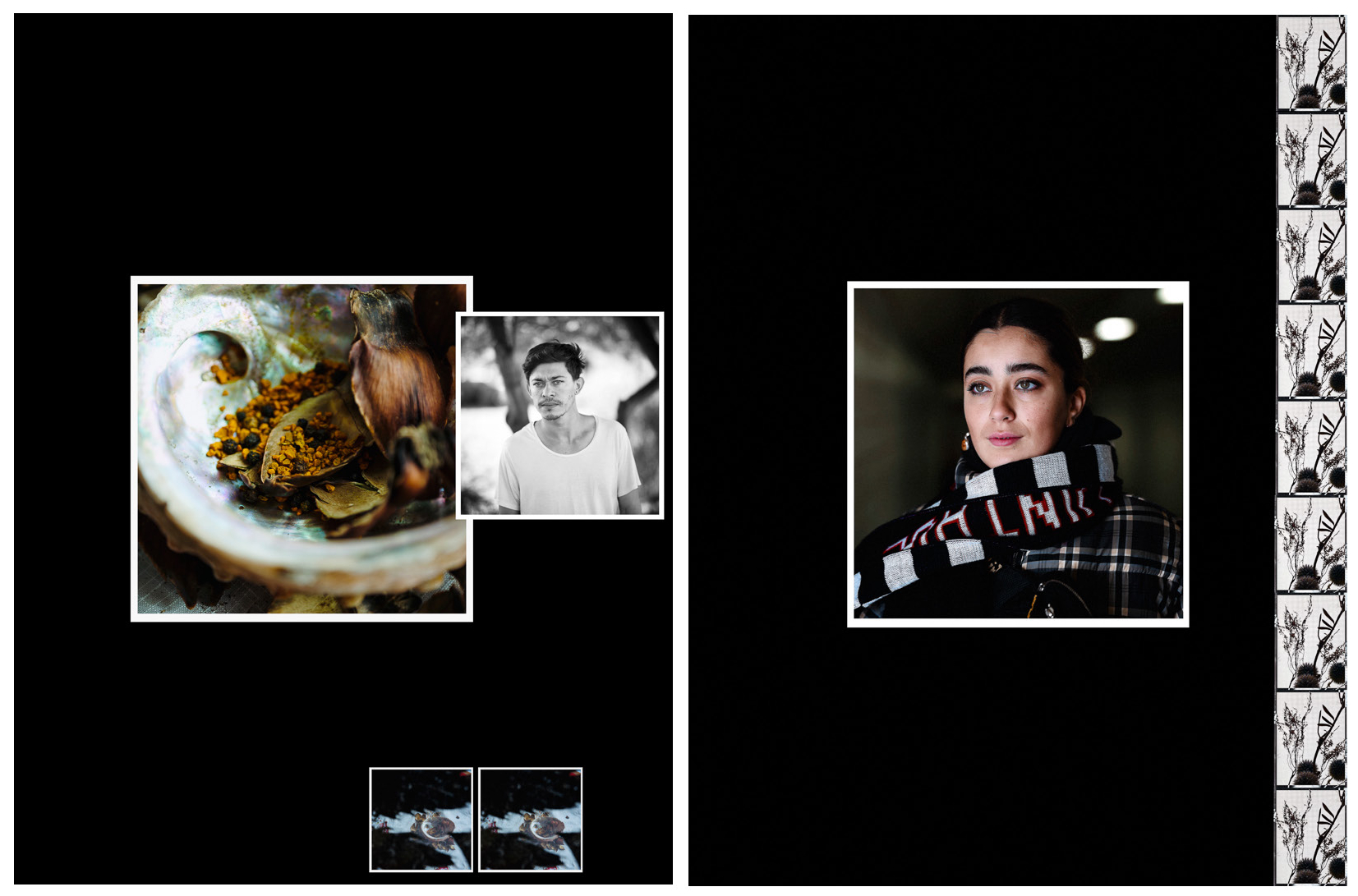

Copyright James Bellorini 2020.

It is of course inevitable that much of the research and thinking in this CRJ during this current module has focused on the directly photographic elements of my practice and its theoretical and aesthetic contexts. Although I have reflected on my thematic context at length across the past year, I haven’t visited it in any great detail in my recent CRJ posts. So, this is a time to rectify that.

For anyone new to my project theme, let me revisit: I am looking at the nature of identity and belonging through the experiences of third culture kids/adults and cross-culture people living in the UK. The work attempts to explore the biomythographical space that directly relates to people of this type of heritage, one that frequently blurs the boundary between fact and fiction. This is a personal exploration (being a UK citizen with an Italian father) and also an exploration alongside those I am collaborating who have connections with, for example, Somalia, Brazil, Iran, The Solomon Islands, Australia, Poland, French Guyana etc.

Biomythography is a term that the writer and activist Audre Lorde created to describe her 1982 book Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. This was, as she recognised, a blend of memoir, history, and myth. It came about because of a misapprehension. Lorde grew up in New York, but her Mother always told her that she was born on an island called Carriacou. Lorde believed this to be a fictional island populated by her Mother’s memories and anecdotes. In later life Lorde discovered that the island was real. Despite this she couldn’t shake the fact that she had been living in a reality built on her own historical fiction, hence a biomythography.

Copyright James Bellorini 2020.

For most of my life (and it turns out this is a frequent experience among both third-culture and cross-culture kids and adults) I never felt I belonged to either specific part of my two cultural heritages. I existed between them in a semi-imaginary world where my identity was in flux, rootless and, at times, profoundly disorientated. It is the exploration of this space that is at the core of my practice. Although I had already been exploring work around this theme during my first tow modules, it was only when I discovered this notion of biomythography during my third module (and coincidentally at the same time as my younger brother and my father passed away), that things began to clarify with regards to the thematic drive behind my project.

The work inevitably crosses into ideas and debates around immigration, racism, populism, genetics, and the meaning of nationality (things that, as I write this, I realise I have been confronting and dealing with all my life). Much of my ongoing background research embraces this subject matter, and has filled my reference list with writers and artists beyond the photographic backbone of the M.A. itself. These include: Nesrine Malik, Benjamin Zephaniah, Nikesh Shukla and others (for references see individual posts and, when published, my end of module complete reference list). It has included research into the nature of social mythologising and the frequently negative outcomes of this, especially where it relates to, for example, the idea of nostalgia and/or conspiracy. In some ways these, especially the nostalgia for a mythological ‘haven’ or land, are an opposing reflection of the biomythographical experience of Lorde: where her island myth was one of foundational growth in her identity (in her case as a gay, black woman), much of our current global conversation is reductionist: shrinking into supposedly historic safe zones cordoned off by borders built of perceived identity. This creates a powerful tension, one that I hope to explore more as I progress towards my Final Major Project. Indeed, the work has a direct starting point in grief and anger, born as it was out of the loss of a world that was once progressing into one of increasing tolerance, but proved to be one of the same old prejudices and fears destabilising once again any notion or hope of belonging for myself and many others.

Copyright James Bellorini 2020.

Looking at my practice, some might argue that a direct documentary approach to represent a project rooted in social exploration would be the way to explore this. And at the outset I thought this might be the case. But, in a mirror of all migrations, the direction of the work held it’s own impetus and for me the subject holds a more constructed approach, one that utilises ‘the validity of fiction as a mode of discovery and experience in and of itself’ (Soutter, 2018, p. 62) to support the experiential breadth and layers of stimuli within the subject matter.

As if to underline this then, I’m going to finish this thematic revisit with a direct quote from an essay by Chimene Suleyman in The Good Immigrant (Shukla, 2016, p. 26) which sums up the kind of diverse experiential elements that have prompted my work:

‘When we cannot return to our homes – or are waiting for them to be taken from us again – we must get the hang of how to recreate it elsewhere. It is in the particular smell of rice, or aubergines, the pastry that survived on the windowsills of our mothers’ kitchens. It is present in the familial catchphrases of a sentence once uttered decades ago, resurrected every mealtime . . . We have been shown to grieve beneath beautiful scarves tied around our hair, and to eat and drink water in back rooms with shut windows so we may not be seen replenishing a life that another has lost. We are heirs to their favourite chairs, and wedding rings, and the noose around their neck.‘

REFERENCES & RESOURCES

- Shukla, N (ed). 2016. The Good Immigrant. London: Unbound.

- Soutter, L. 2018. Why Art Photography? 2nd edn. London: Routledge.